An Ebola Outbreak In The Democratic Republic of the Congo Has Been Contained With Astonishing Speed

A lesson in the value and utility of multilateralism

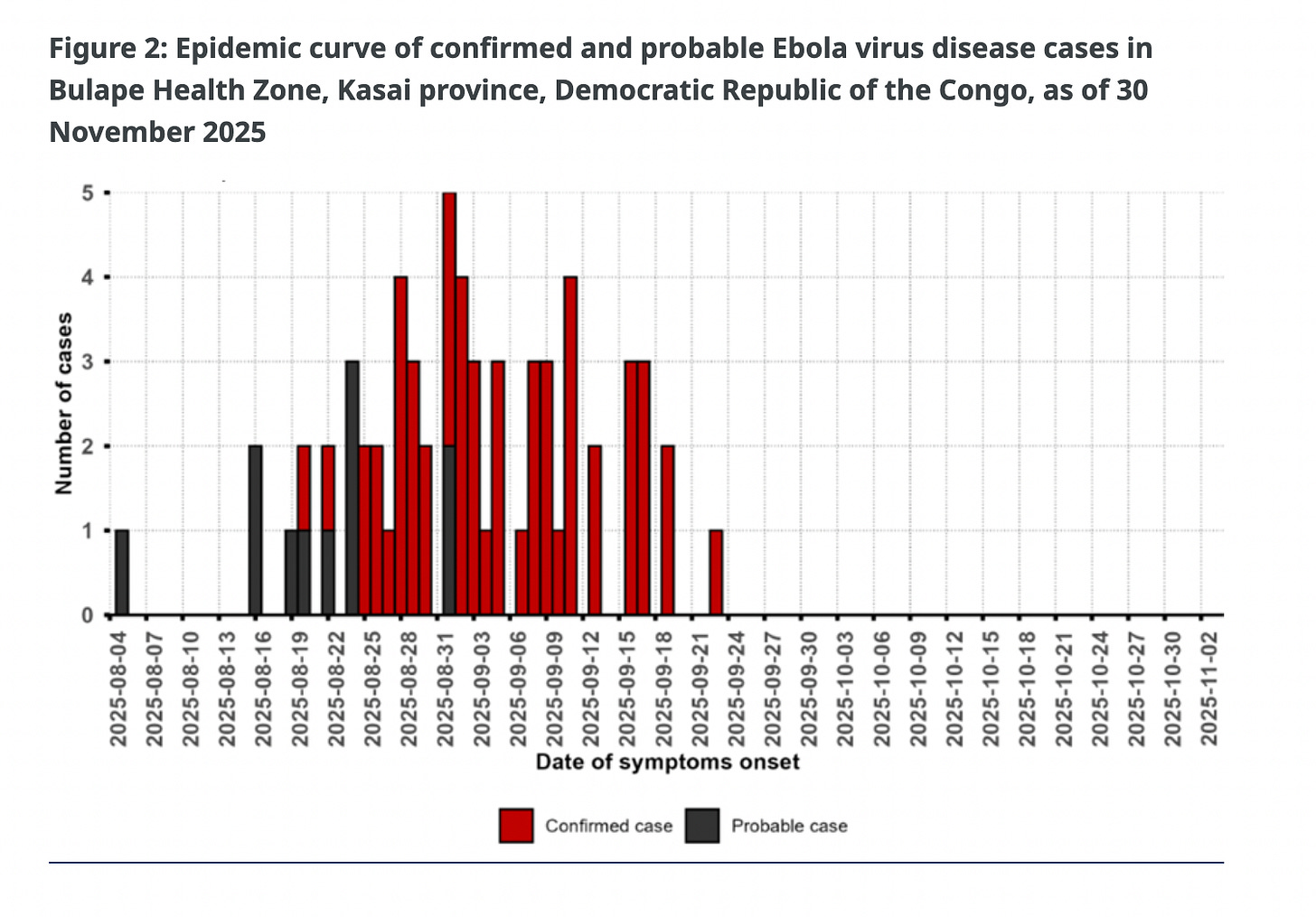

A once menacing Ebola outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo has been brought under control. Though it barely made news in the Western press, on December 1st Congolese health authorities declared that an outbreak that infected 64 people — 45 of whom died — had successfully been contained.

Credit for stopping this outbreak goes first and foremost to local and national health officials. When a suspected case — a 34-year-old pregnant woman — was admitted to a rural hospital in the central province of Kasai with symptoms on August 20, national authorities quickly identified it as Ebola and declared an outbreak.

What unfolded next offers a clear illustration of how the international health system is supposed to work during a crisis: actors across borders moved quickly, coordinated effectively with national authorities, and deployed the tools necessary to prevent a local outbreak from becoming a regional or global catastrophe.

It was a glimpse of what global cooperation can achieve — and what may be lost if that system falls apart.

A Lot of Multilateralism Went Into Stopping this Ebola Outbreak

Since the devastating West Africa Ebola outbreak in 2014–2016, the world has developed a series of procedures and tools to prevent local outbreaks from spreading. Arguably the most important of these are new Ebola vaccines. Medical workers in many African countries receive these vaccines, which reduces risk for those on the frontlines. They then embark on a “ring vaccination” strategy, vaccinating people who may have come into contact with an Ebola patient. This strategy has been remarkably effective at stopping the spread of Ebola in the numerous outbreaks since 2016.

But the vaccine — and its deployment — did not simply emerge from the ether. The vaccines themselves were developed by international consortia of scientists, and they are purchased and made available by the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunization (Gavi), an international body that supports the development and provision of vaccines for low-income countries.

In the case of this recent outbreak, Gavi deployed 48,000 vaccine doses from its global stockpile, which quickly reached the affected region. Then came the hard work of actually identifying contacts and getting the vaccine to the people who needed it. Here, another multilateral entity — the Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI) — played a key role. GPEI dates back to the late 1980s, when polio was paralyzing hundreds of thousands of children around the world, despite an effective vaccine that had eradicated it in wealthier countries. This year, there were fewer than 75 total wild polio cases worldwide — including zero in the Democratic Republic of the Congo — thanks in large part to the logistics, surveillance, and inoculation efforts undertaken by GPEI in partnership with local authorities. When this particular Ebola outbreak was declared, GPEI tapped these networks and put them to use in service of stopping Ebola. And it worked.

Even if a ring vaccination campaign succeeds, by definition it means there are people already infected with Ebola. They need treatment. Ebola has a devastating mortality rate — in this case, upwards of 70% of people confirmed to have the virus succumbed to it. But the death rate is not 100%, and containing an outbreak requires people to seek treatment and not remain in their communities where they may spread the virus to loved ones.

Here, yet another innovation born of international cooperation was deployed. For the first time in the midst of an outbreak, an experimental field treatment facility was established. The Infectious Disease Treatment Module was developed by the World Food Programme and the World Health Organization as a portable field hospital designed specifically to treat infectious diseases in logistically challenging environments. It was prototyped, designed and tested under UN auspices, and successfully deployed for the first time this year to respond to this outbreak.

At the center of these multilateral efforts, of course, was the World Health Organization, which deployed over 100 responders to the affected region and coordinated the international response.

Needless to say, all this international cooperation worked! “Controlling and ending this Ebola outbreak in three months is a remarkable achievement. National authorities, frontline health workers, partners and communities acted with speed and unity in one of the country’s hard-to-reach localities,” said Dr. Mohamed Janabi, WHO Regional Director for Africa, in a statement marking the end of the outbreak. “WHO is proud to have supported the response and to leave behind stronger systems, from clean water to safer care, that will protect communities long after the outbreak has ended.”

December 1st was the day that this outbreak could officially be declared over because no new cases were detected after a standard waiting period following the last confirmed case. But in reality, this outbreak was contained much sooner than that. Withing about a month from the first confirmed case this outbreak was firmly under control.

This is astonishingly fast. And that speed was achieved because Congolese authorities and multilateral platforms with whom the government partners — GAVI, the WHO, and others — have built systems designed to confront an outbreak like this. This took forward-looking investments and in this case those investment paid out big time. The 2014-2016 ebola outbreak killed over 11,000 people and is estimated to have cost economies $54 billion. This outbreak, on the other hand, was quickly contained before it could spread and wreak havoc across the region, or world.

This is what a successful international response to a deadly disease outbreak should look like. But it is not clear whether such a success can be replicated. For decades, the United States was the largest funder of the multilateral health platforms that helped drive this response. Over the past 11 months, however, GAVI has been defunded by the Trump administration, as has the Global Polio Eradication Initiative. The administration has also withdrawn the United States from the World Health Organization and prohibited American officials from cooperating with it.

For now, these entities rose to the occasion, demonstrating that international cooperation is not simply an ideal to which countries should aspire, but a practical necessity for confronting public health emergencies. Their success should be recognized, but it should also come with a warning: unless these platforms are adequately supported, their ability to repeat this kind of success is far from assured.

I like to keep this kind of solutions journalism free for all subscribers. But if you appreciate the kind of humanitarian journalism I do, please support Global Dispatches with your paid subscription. You can buy a subscription at full price or using the discount link.

Hopeful post. Thank you.