Darfur Genocide Watch

"Never Again" is Happening Again -- A New Series.

Author’s note. I cut my teeth as a journalist in the mid-aughts covering the international response to the 2003-4 Darfur Genocide. Today, the same forces responsible for the Genocide are back in action, wreaking destruction in Darfur in ways reminiscent of 20 years ago. This piece draws on over 17 years of my reporting, and is Part One of an ongoing series that we’re calling “Darfur Genocide Monitor.”

A systematic and organized campaign of ethnic cleansing is again underway in Darfur. We will bear witness by offering original reporting and expert analysis. To support our work purchase or upgrade your subscription.

A Brief History of the Darfur Genocide

Genocides always happen in the context of a war.

April 25, 2003 is generally regarded as the day the Darfur war began. With a list of grievances going back decades, rebel militias from Darfuri tribes launched a spectacular raid on an Air Force base in el Fashir, Darfur's largest city. Government forces were taken by surprise. By the end of the fighting, scores of government soldiers lay dead, the base commander was captured, and a fleet of helicopters and bombers laid destroyed on the runway.

The central government in Khartoum was slow to respond. In part, this was a consequence of geography. Sudan in 2003 was the largest country in Africa. Darfur, which is composed of the three provinces of Sudan's western-most region, is a vast, unforgiving arid region the size of France. And at the time of the attacks on el Fashir, the bulk of Sudan's military was fighting a protracted civil war in Sudan’s south, far from Darfur.

Throughout the spring and summer of 2003 rebel armies exploited these weaknesses and sacked a number of government installations, looting their armaments and gaining strength after each attack. By the end of the year the rebels had de-facto control over much of rural Darfur.

Lacking the resources to take on the Darfur rebels directly, the government sought an alternative strategy: They would exploit local ethnic tensions to their advantage.

Desertification in western Sudan was increasingly pitting historically nomadic Arab tribes in competition for water and arable land with non-Arab tribes of Darfur, armed groups of which were now mounting a rebellion. The ruling clique in Khartoum were also ethnic Arabs and sought to exploit these long simmering tensions. Emissaries from Khartoum traveled to Darfur and met with Arab tribal leaders, bundles of cash and guns in tow. Well armed militias began to spring up throughout Darfur. Soon, non-Arab Darfuris began calling the militiamen Janjaweed, or “devils on horseback.” By the spring of 2004, these devils, supported by the central government, turned Darfur into hell on earth.

"I’ve seen the remains of people who were locked inside their homes as it was burned to the ground," Brian Steidle, then a 29-year-old former U.S. Marine Captain told me in March 2005. (I’ve been covering this story a very long time). Steidle was one of the first Americans to witness the violence in Darfur first-hand. In 2004, he was hired as an advisor to a tiny African Union monitoring mission in Darfur. Armed with only a camera, Steidle documented the horror.

In one time-lapsed series taken from a helicopter hovering above the town of Labado, Steidle depicts a typical attack. First, a Sudanese government reconnaissance plane passes over the target. Then, two helicopter gunships move in, strafing the town of 20,000 and firing on people indiscriminately from above. Finally, a Janjaweed cleanup crew moves in.

This is when the brutality escalates. In March 2004, town of Kaleik fell to Janjaweed forces. A grim report from UN human rights investigators describes what happened next.

Government forces and Janjaweed attacked at around 15h00, supported by aircraft and military vehicles. Again, villagers fled west to the mountains. Janjaweed on horses and camels commenced hunting the villagers down, while the military forces remained at the foot of the mountain. They shelled parts of the mountains with mortars, and machine-gunned people as well. People were shot when, suffering from thirst, they were forced to leave their hiding places to go to water points. There are consistent reports that some people who were captured and some of those who surrendered to the Janjaweed were summarily shot and killed. One woman claimed to have lost 17 family members on the mountain. Her sister and her child were shot by a Janjaweed at close range. People who surrendered or returned to Kailek were confined to a small open area against their will for a long period of time (possibly over 50 days). Many people were subjected to the most horrific treatment, and many were summarily executed. Men who were in confinement in Kailek were called out and shot in front of everyone or alternatively taken away and shot. Local community leaders in particular suffered this fate. There are reports of people being thrown on to fires to burn to death. There are reports that people were partially skinned or otherwise injured and left to die.

But Was it “Genocide?”

On February 18, 2004 the relief organization Doctors Without Borders/Medicines Sans Frontieres warned of "catastrophic mortality rates" in Darfur. Earlier, the UN Undersecretary General for Humanitarian affairs Jan Egeland called Darfur "probably the worst humanitarian catastrophe in the world" and predicted that 1 million people may have already been displaced by the fighting. Then, on February 24, Eric Reeves, a longtime Sudan activist and English Literature professor at Smith College, wrote an op-ed that seized attention in official Washington. "Immediate plans for humanitarian intervention should begin," urged Reeves in a Washington Post op-ed. "The alternative is to allow tens of thousands of civilians to die in the weeks and months ahead in what will be continuing genocidal destruction."

With that statement, the Reeves became the first American commentator to invoke "genocide" when speaking of Darfur. By the summer hundreds of thousands of refugees were fleeing across the border into Chad. High level State Department officials began to take serious notice.

The question of genocide loomed large, but officials still lacked basic information about the scope of the atrocities. In June, the Ambassador at Large for War Crimes Issues Pierre-Richard Prosper and the Assistant Secretary of State for Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor Lorne Craner invited the Coalition for International Justice, a Washington-based non-profit that provides technical support to international war crimes tribunals, to a meeting at the State Department. Prosper was a former prosecutor at the Rwanda war crimes tribunal. Craner had a background in polling. They asked the group to devise a survey tool to determine the nature and scope of the killing in Darfur.

“There was a big push … to interview refugees to determine was actually going on in Darfur,” Stephanie Frease, a former Coalition for International Justice employee, told me in 2005. “And they wanted to act quickly.” By July, the newly formed Atrocities Documentation Team was on the ground in eastern Chad, interviewing thousands of Darfur refugees. Armed with a multi-page questionnaire, the team sought to find empirical evidence that could confirm claims of genocide.

In mid-August, the team sent their findings back to Foggy Bottom. The data clearly showed that non-Arab Dafuris were being targeted en mass. But alone that was not sufficient to determine that the crimes amounted to genocide. Rather, "intent" to commit genocide had to be determined as well, and this was more difficult to prove through a statistical survey of victims. So, on a Saturday afternoon in mid-August, Secretary of State Colin Powell called Prosper at his home — the Genocide Convention in hand — to discuss the tricky question of "genocidal intent."

The next day, Powell summoned his top staff in a conference call to let them know that that he believes the crimes in Darfur amounted to genocide. On September 9th, Powell went public with this information. "Genocide has been committed in Darfur," Secretary Powell told the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. "The government of Sudan and the Janjaweed bear responsibility—and the genocide may still be occurring."

That declaration made headlines, but did not actually trigger any meaningful change in US (or European) policies towards Sudan in 2004. “Genocide” may have been declared, but the status quo remained.

By the end of 2005, fighting on the ground in Darfur had subsided. The Sudanese government's counter-insurgency-by-genocide had worked. The rebel movements were languishing, and the civilian populations from which they came had been largely uprooted. The conflict had entered a new phase, one that Eric Reeves coined "genocide-by-attrition." Starvation and disease, rather than direct violence was the prime killer of Darfuri civilians, 2.5 million of whom by now lived displaced persons camps in Darfur and Chad.

In all, the United Nations estimates that 300,000 people were killed in the 2003-2004 Darfur Genocide. The International Criminal Court would indict the top Janjaweed leader and the former dictator of Sudan, Omar al-Bashir, for the crime of Genocide. Neither have seen the inside of a courtroom in the Hague.

A New Darfur Genocide?

Having proven themselves on the battlefields of Darfur, the Janjaweed became folded into the security architecture of Omar al-Bashir’s dictatorship. In 2013, the erstwhile Janjaweed were rebranded the “Rapid Support Forces” and would report directly to Bashir’s intelligence chief. The RSF became a paramilitary distinct from the regular Sudanese Armed Forces. Their leader was a former Janjaweed commander Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, better known as Hemeti.

For the past ten years, things have been going very well for Hemeti. His battled-hardened Rapid Support Forces became a regional army-for-hire, rented to the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia to fight on behalf of Gulf interests in Yemen and Libya. Meanwhile, the RSF seized control of large gold mines in Darfur. Hemeti soon became one of the most powerful — and one of the wealthiest — men in Sudan. But as Hemeti amassed wealth and power, the chief of the Sudanese Armed Forces (the other army in Sudan) grew resentful.

War returned to Sudan in April 2023 when the RSF and the Sudanese Armed Forces turned their guns on each other, vying for control of Sudan. Omar al-Bashir had been toppled in a popular coup five years earlier and for a time, the RSF and Sudanese Armed Forces were allied in an effort to prevent civilians from taking control. But on April 15, the RSF and Sudanese Armed Forces engaged in vicious battles on the streets of Khartoum.

The fighting soon spread to Darfur.

Within months the Rapid Support Forces were unleashing a pattern of violence that harkened to the genocide 20 years prior. By June, the head of the Holocaust Museum’s Simon-Skjodt Center for the Prevention of Genocide Naomi Kikoler warned, “Darfuris again are at risk of genocide and…today’s perpetrators have ties to the same actors who perpetrated the first genocide.”

Evidence of New Atrocities in Darfur

By August 2023, there is mounting evidence that the Rapid Support Forces are pursuing a campaign of ethnic cleansing in Western Darfur, targeting non-Arab tribes — specifically the Masalit people.

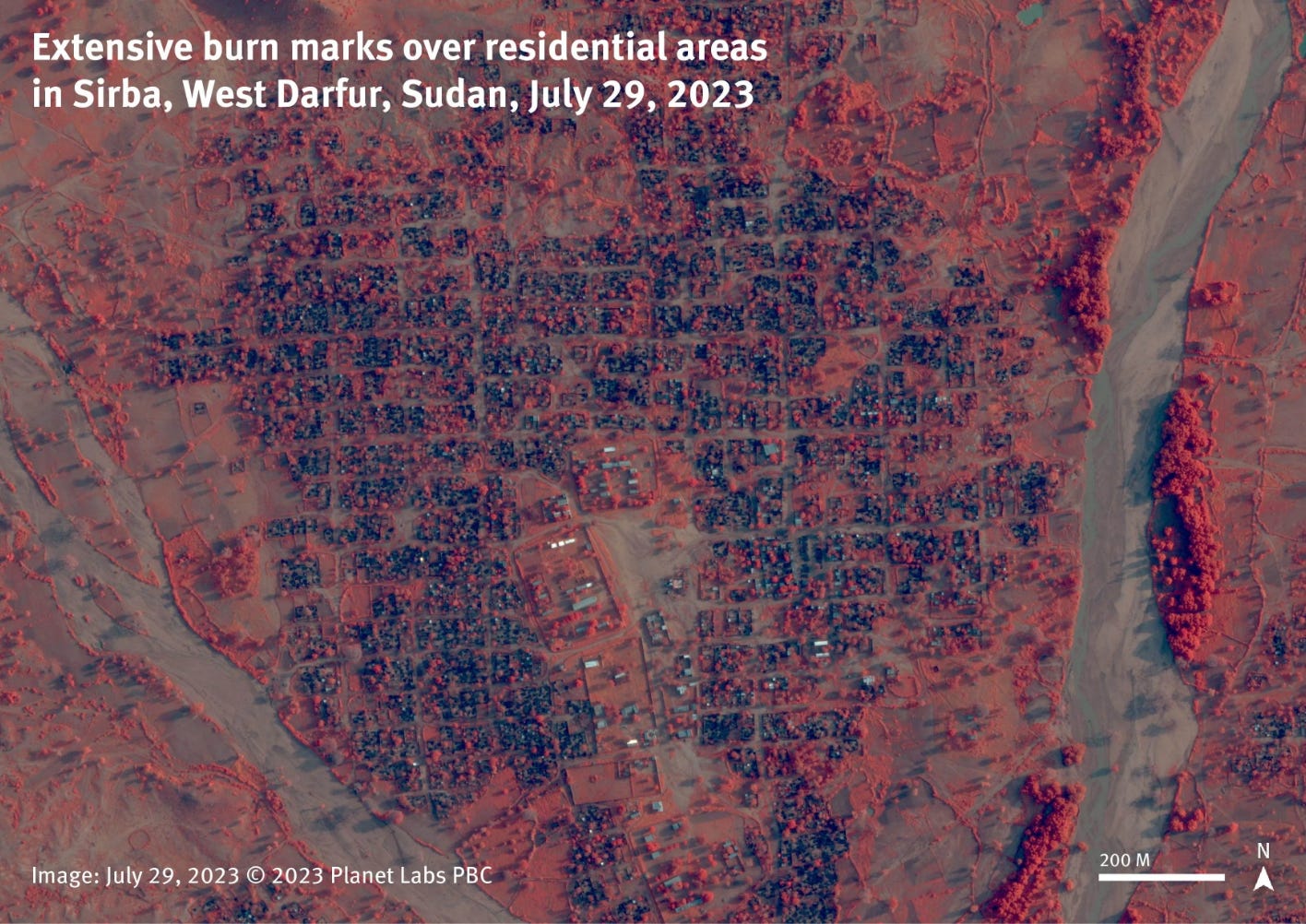

“What we are seeing now is the RSF and allied Arab militias beginning a campaign of extreme violence and even ethnic cleansing, certainly in parts of West Darfur largely targeting Masalit communities there.” Cameron Hudson, a former CIA Intelligence Analyst and State Department official now at the Center for Strategic and International Studies tells me in a podcast interview this week. “We're hearing reports of destruction of villages, seeing satellite imagery again of burning villages. We're discovering mass graves to the extent that people have access to the region…villages being entirely wiped out by these militia attacks…A lot of the same elements that we saw 20 years ago are replicating themselves again — the same victims in many cases and the same perpetrators”

The publicly available evidence of atrocities is starting to pile up.

Since the civil war in Sudan broke out April, some 380,000 people have fled across the border to Chad, mostly from West Darfur. Like in 2003, humanitarian groups in general —and Doctors Without Borders/Medicines Sans Frontieres in particular — have been our best source of information about what these refugees experienced. After receiving hundreds of war wounded in an MSF hospital across the border in Chad, staff began to collect testimonies from the mostly ethnic Masalit victims of the RSF and allied militias.

On August 1, MSF sent these testimonies to reporters, providing clear evidence that civilians are being targeted by the RSF on the basis of their ethnicity.

"At first, I had no plan to leave El Geneina. Me and my two daughters along with my mother and four of my sisters moved to a collective shelter in the Al Madares neighborhood […] Then, Arab militias attacked us in the shelter. They told us that this wasn’t our country and gave us two options: immediately leave for Chad or be killed. They took some men and I saw them shooting them in the streets, with no one to bury the corpses. So we fled in a big group.” — H

“At Shukri, a small group stopped us and asked us to sit down. It was like Judgement Day. I was scared, I prayed to God to get me out of there alive. [They said], ‘All slaves must stand up and if you want to live, leave Sudan because Sudan is for Arabs.’ We started running and the armed men were shooting at people at random [...] Everywhere I looked, I saw death. Believe it or not, death has a smell, and I could smell it. I saw many corpses on my way. I thought I might be joining those corpses in a few moments. But fortunately, we reached the border. That's when I saw a white SUV belonging to Médecins Sans Frontières, which picked me up and took us to the hospital in Adré, where I was treated and looked after.” — C

In addition to these first hand accounts, a report from the UN’s Office for the High Commissioner for Human Rights confirmed a mass grave containing the remains of 87 Masalit killed by RSF in the middle of June. More recently, satellite imagery has documented the whole-scale destruction of Masalit villages in Western Darfur.

The image comes via Human Rights Watch, which notes that this the seventh such village burned to the ground in West Darfur in recent weeks.

It’s a tactic—and imagery — eerily similar to what Brien Steidle captured 19 years prior. And that is the point: It’s happening again. A systematic and organized campaign of ethnic cleansing is underway in Darfur and the outside world is barely paying attention.

Let’s change that.

Global Dispatches will bear witness, offer original reporting, and give you the analysis and context you need to understand this crisis as it unfolds. In future editions of Darfur Genocide Monitor you can expect updates from my sources on the ground in Sudan and beyond, expert analysis about what is driving this conflict, and solutions-focused journalism on how to stop this crisis from deteriorating further.

To do this, we need your help. Please support this reporting project through a paid subscription to Global Dispatches.