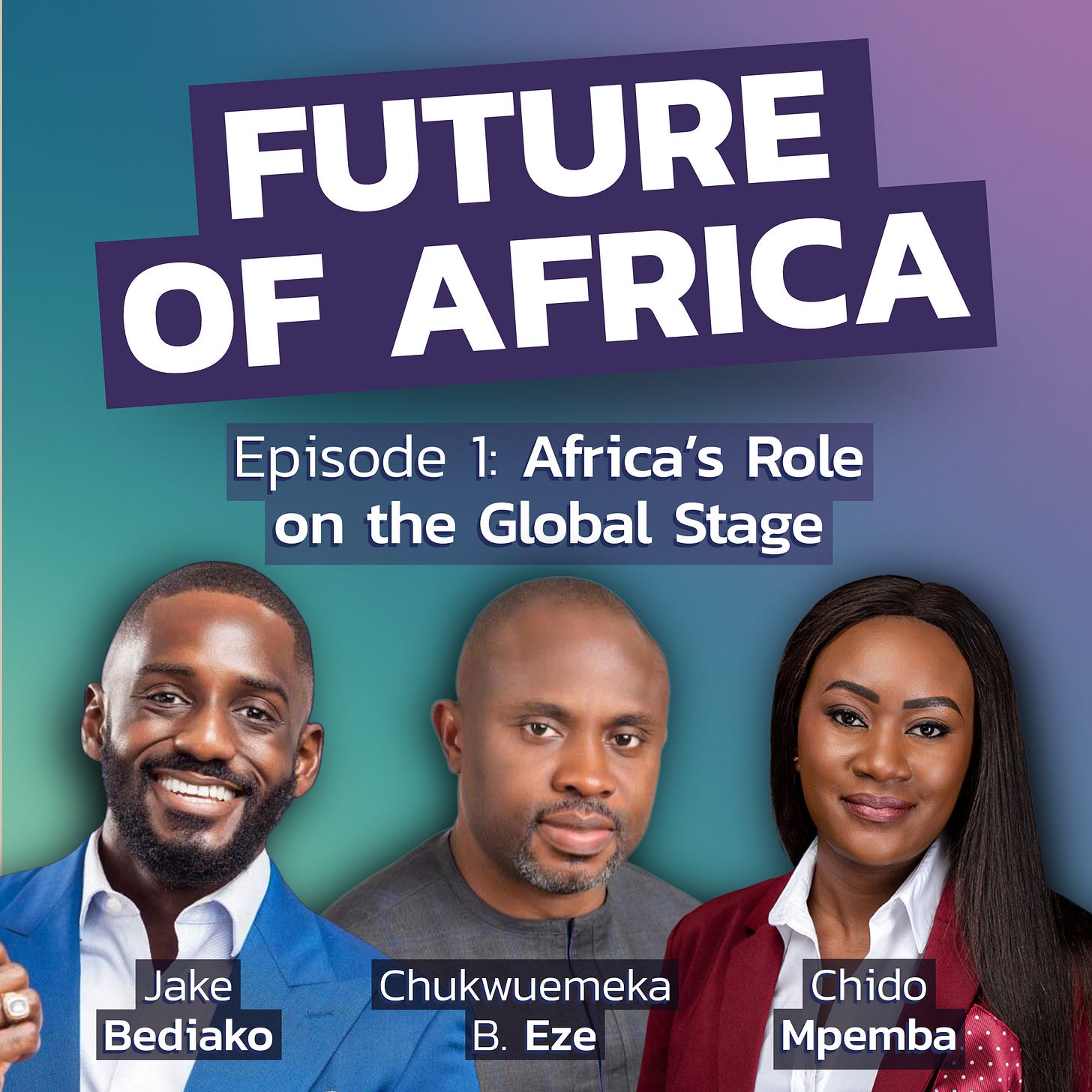

Episode 1: Africa’s Role on the Global Stage

The debut episode of the Future of Africa podcast series

Africa’s influence on global decision-making is rising as the world’s youngest and fastest-growing continent — but will young people be given the power to shape it? Chukwuemeka Eze lays out why legitimacy at home is the foundation for influence abroad, while Chido Mpemba champions young people’s leadership in every sphere of governance. Jake Obeng-Bediako warns against “waithood” as the lost years between education and meaningful leadership, and calls for young Africans to be decision-makers. Together, they highlight ways young African countries are navigating geopolitical shifts, increasing their role in multilateral forums, and leveraging demographic and economic momentum. This is a call-to-action for anyone who believes Africa should lead as an innovator on the world stage.

Subscribe now on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or wherever you get your podcasts. And be sure sign up for our newsletter to get each new episode and transcripts delivered straight to your inbox.

Guest Speakers

Jake Bediako, Director of Policy and Implementation for Global Citizens Move Afrika Initiative.

Dr. Chukwuemeka Eze, Director for Democratic Futures in Africa at the Open Society Foundation

Chido Mpemba, formerly the African Union’s Special Youth Envoy and currently the Advisor to the African Union Commission Chairperson for Women, Gender and Youth.

Background Materials

Explaining the Current Path, ISS African Futures and Innovation platform

Shape Africa, Office of the African Youth Envoy

Three Major Africa Initiatives, Open Society Foundation

Mark Leon Goldberg:

Welcome to The Future of Africa — a special series on Global Dispatches. I am Mark Leon Goldberg, the host and founder of Global Dispatches. And in several episodes over the coming weeks, we will bring you in-depth conversations designed to explore Africa’s future in the context of today’s challenges and opportunities. This series is produced in partnership with the African Union, The Elders, and the United Nations Foundation, and is hosted by the Kenyan journalist Adelle Onyango.

I am truly thrilled to bring you this special project of Global Dispatches. We have some amazing guests in this episode and throughout the series. Enjoy!

Adelle Onyango:

Welcome to the Future of Africa, a show where we uncover the ideas, movements, and people who are shaping the continent’s next chapter. I’m your host, Adelle Onyango, and in this premiere episode, we’re exploring Africa’s rising global influence — Not in theory, but in real time. From the African Union to grassroots movements, a new wave of African voices are redefining how the continent shows up on the world stage.

Joining us for this conversation are three leaders who each bring a unique perspective to this shift. First is Dr. Chukwuemeka Eze. He works at the Open Society Foundation and has more than two decades of experience. He’s helped shape peace and governance frameworks across the continent, and continues to champion citizen-led, locally rooted diplomacy.

Dr. Chukwuemeka Eze:

Our leaders who fail to understand this are on the wrong side of history because this is championed by a new generation of leadership.

Adelle Onyango:

We’re also going to be hearing from Chido Mpemba. She’s a former African Union Special Youth Envoy, and now is the Advisor to the AU Commission chairperson on women, gender, and youth. Chido brings sharp insights into how young Africans are shaping multilateral partnerships and making their voices heard at the highest levels.

Chido Mpemba

How can we educate and engage, including with our African Member States, to ensure that in whatever meeting is being held, it’s inclusive of the young people being on the table?

Adelle Onyango:

Last, but definitely not least, we’re going to be joined by Jake Bediako, the Director of Policy and Implementation for Global Citizen’s Move Africa Initiative. He’s a former presidential advisor in Ghana. And Jake represents a generation of young Africans entering public service with the intention to shift systems from the inside, and also roping in Africans in the diaspora.

Jake Bediako:

So, if Africa is serious about young people in positions of power, we are going to need a societal communal overhaul of how we even think about young people and our capabilities.

Adelle Onyango:

Together, they impact how inclusive governance, intergenerational collaboration, and bold leadership can amplify Africa’s voice globally, and why now is the time to act. So, let’s get into it. First off, let’s hear from Dr. Eze.

Adelle Onyango:

So, Dr. Eze, thank you for making time to be with us and to have this conversation with me.

Dr. Chukwuemeka Eze:

Thank you so much for having me. But let me also correct that that position later changed to Director for Democratic Futures in Africa.

Adelle Onyango:

Got it. Thank you for that correction. And it sounds like the correction is even in line with the conversation because we’re looking at where are we going as a continent. But let’s start with the president. So, I’m coming to you from Kenya. And we have, for the past over a year, been having a lot of protests, a lot of active citizen conversations, a lot of back and forth about government, and sometimes it feels like, and this is not unique to Kenya, that citizens’ opinions and perspectives are not being taken account by the government, which is dear to specifically Kenya.

Because if you look at our pre-colonial times, even our culture back then was very attuned to democratic practices — so we had, like the council of elders, we had a communal way of engaging, we had consensus building. And so, I guess that’s why we resist it more when we feel like that’s not what we’re getting. But when we talk about democratic resilience, many people don’t think about the importance of understanding citizens’ perspectives and their perceptions of the government.

Why do you think this is key and critical and not only for governments to take into account, but it’s critical for us to improve and strengthen our influence internationally?

Dr. Chukwuemeka Eze:

I remember clearly that in a recent lecture delivered by the president of Open Society Foundations, she unambiguously stated the ideals of an open society, human rights, equity, and justice are under threat, and that there is greater polarization and the spirit of global solidarity, which has given way to fighting levels of insularity in many places. One thing that, in my opinion, we must be clear about is that Africa is witnessing the emergence of a new political dispensation. And our leaders who fail to understand this are on the wrong side of history because this is championed by a new generation of leadership, new political cultures, and new forms of people power.

And they are rendering creative districts unnuanced strategies and providing same in places and processes, which could disrupt historical and new anti-democratic forces. They’re building new leadership and offering alternative ways of doing politics in ways that foster social cohesion. So, what is happening in Kenya, Nigeria, South Africa, where this new generation of leaders, I imagine, is simply organic because this could now lead the foundation of a broad-based new social contract with the reformed African states, which will reform African states. Because, as a political scientist, I’ve always argued we don’t have African states. What we have is states in Africa. No states in Africa developed organically. So, this, in my opinion, is a unique opportunity that must be understood for Africa to leverage and remain relevant in international politics, governance, and diplomacy.

Understanding citizens' perception of governance, democracy and leadership is important. Not just for building better societies at home, but for Africa’s credibility and influence abroad. And it is no longer enough for government to meet technical benchmarks. If people feel excluded on head or hand, the legitimacy of those democracies fall apart. This has real consequences for how Africa is received and respected globally. So, Africa’s local democracy and governance must stand out as mirroring international best practices and standards. And if you take a good example at African Union and other supranational institutions, with their peace and security architecture and governance frameworks, they have struggled to enforce their own norms. SADC’s response or indifference to the crisis struggle of people of Zimbabwe, Mozambique, and Eswatini, ECOWAS’ loss of three of its members to the Alliance for Sahelian States are all very sobering examples. So, if Africa wants to lead globally, it must first prove that it can uphold its own rules and reflect the democratic aspirations of African citizens. International influence starts with legitimacy at home.

Adelle Onyango:

Yeah, and Dr. Eze, it’s so interesting. I’ve never heard that before. You’ve really given me food for thought specific to, in a very generic way, states being formed right now, and that being an opportunity for us to really change the course of history for Africa. And I agree with you because, for the first time, it’s very easy to get a feel of what citizens of a particular country feel.

If we look at digital platforms have made that so much easier. So, if you want to influence outside of your country, yet we can get firsthand top-level knowledge of what your citizens are feeling, which wasn’t the case before, and they are doubting you, it kind of chips away at your ability to influence anyone. So, I completely agree with you on that.

When we talk about these issues, accountability and transparency have been said to be the lifeblood of democratic resilience, right? I know you’ve touched on it, but maybe we could speak to three to five ways in which African nations can build stronger democratic resilience in the face of the different pressures, be it external or internal pressures. And perhaps a good place to start is to talk about the internal and external pressures that the nations are facing.

Dr. Chukwuemeka Eze:

As nation states continue to progress amidst divergent political influences, struggle for superiority, and borrowing from youth technological advancements, political interests and socioeconomic cleavages and, more importantly, the complexities of state-to-state relations and the entrusted politics which continue to deepen. My belief is that the capacity of states to respond adequately to growing internal and external pressures and challenges will depend on its strategic alliance and inclusive approaches to governance. Let me share maybe four key lessons through the lens of my current role as the Director for Democratic Futures in Africa at Open Society Foundation. Lesson number one — Democracy is not gratification. Bold choices build democracy up. I often think about democracy and autocracy. And you are from Kenya, so you will understand it better than I do as a relay race.

The only difference is that the autocrats jump the gun, getting ahead early while the Democrats are still deciding what to do. But Democrats, when they eventually move forward, can hand over the baton to fresh legs. Every team member contribute their skills and expertise. They cheer each other on. And, as the saying goes, this is an African cliché — if you want to go fast, go alone. If you want to go far, then go together. That’s democracy in a nutshell. Hard work pays off. And we must begin to build on those elements that provide stable democracies. The second lesson is that to establish inclusive, socially cohesive, right-based and just African democracy is rooted in ubuntu, which, in your opening, you already alluded to, is an Africa philosophy for reciprocal, mutual, and solidarity-based humanism and dignity.

We must invest in reimagining politics and governance by strengthening the organizational and mobilization of power of diverse intergenerational and intersectional constituencies, such as youths, women, trade unions, social movements, artists, traditional civil society, peri-urban and rural communities. And not just the elites in Nairobi, in Lagos, in Abuja, in Johannesburg, and so on and so forth. The third lesson is that global order that once promised mutual accountability is flattening. You can imagine Russia’s war on Ukraine that continues to rage. The Israeli onslaught and assaults on Gaza has claimed thousands of lives. Even stable democracies have veered into illiberalism.

So, building a resilient democracy therefore requires strengthening the power of citizens to organize and mobilize beyond this historical identity and cleavages based on shared economic value and visions, which can remedy historical fragmentation from ethno-regional, religious, gender and class identities; in turn, focusing on mutually agreed socioeconomic rights, therefore, demand an alternative economic vision, which will enable social movements and civil society activism and political actors to evolve what I call peoples manifesto.

Drive policy and institutional reforms agenda, as recently witnessed in Kenya, Nigeria. The last lesson, which also touches on some of our intergovernmental organizations, is that nowhere is democratic backsliding and illiberalism more visible than in parts of Africa. In the last four years, Sudan, Gabon, Guinea, Conakry, Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger have all experienced some kind of political instability and military takeovers.

Many coincidentally greeted not their outreach, but with popular support. What’s more, the latter three countries I mentioned, which remain under military rule, have withdrawn from the regional economic communities and accused ECOWAS of docility. So, whenever this happens, my reading is that people are not welcome in the military. People are welcoming a new hope when democracy has failed. So, this is not an endorsement of authoritarianism. Rather, it is a rejection of democracy that has failed to deliver dignity, livelihood, or justice. And we must learn from this and build better democratic futures in Africa.

Adelle Onyango:

That’s so interesting because when you see people leaning towards military rule, becoming more popular with citizens, it is that. It’s a welcoming of something that’s different. It’s a lack of feeling like the previous regimes have let you down. The previous systems do not work, and so this is our only hope. And so you’re right — that actually speaks to just the breakdown, the breakdown in democratic resilience.

I wonder if we could go into citizens because now we’ve touched on our reaction to what comes in place after the failure on the promises that governments that were in charge have had. What role do citizens play in safeguarding democracy resilience? Because a lot of times, the energy and the attitude that we have is that these things are happening to us and that we have no power. So, what role would you say citizens play in this?

Dr. Chukwuemeka Eze:

So, here is the catch — We have a demography of a median age of 18 and a projected population of 2.5 billion by 2050. So, when we are talking about citizens, let us be specific that we are looking at this demography, and not just the old politicians. So, when I hear the cliché that the future belongs to this demography, I always counter it by saying today actually belongs to them.

Adelle Onyango:

Yes.

Dr. Chukwuemeka Eze:

And they are no longer waiting to be given that hope. They want to see this hope today. But if we don’t leverage this demography, then it becomes a source of instability and frustration. So, if we are serious about amplifying Africa’s voices in multilateral forums, then the young people should no longer be giving what you call a tokenized participations. There needs to be sharper, there need to be more intentionality about how we deal with them. So, the current generation of what we have does not add up if you look at this demographic. So, a deliberate effort to rebuild a collective sense of identity that surpasses parochial division of religion, tribe, ethnicity, and race is important. And I think that if you, for example, should champion this.

Also included in this is the assumption that the effort geared towards the strengthening of dialog spaces and platforms through the application of accessible digital technology, civic education beyond national level to subregional level is important for constant stakeholders engagement. The citizens no longer should depend on politicians’ manifesto as what should deliver democracy. It is only in our work line that I see the employers of labor depend on the employees to tell them what to do.

We only argue about politicians’ manifesto whether they’ve delivered or not. So, if you ask me, we are talking about democracy within the context of social contract. Who designs the social contract? What is the terms of reference for the social contract? So, citizens need to sit down and articulate a plan of action, whether they’re extracting it from the AU Agenda 2063 or National Development Plans.

They should be the ones not telling the politician, “Drop your manifesto. This is the citizen’s manifesto that should guide your operations.” And then monitor and evaluate performance. The politician understand this. And that’s why when they say we are engaged in participatory democracy, it is participatory democracy as defined by them rather than defined by the citizens. We must champion programs and activities that now strengthen public institutions that support and sustain democracy, such as judiciary, security sector, to function effectively. And no longer shall we, as citizens, continue to abide by this principle of state security over and above human security, or what you can call citizens welfare.

Adelle Onyango:

You know what, Dr. Eze? This is so true because even issues around public participation, you will find that your country, again, I’ll just say Kenya because this is where I’m from and it’s the context I understand very well — we have an incredible constitution, and that constitution enables us as the citizens to hold these leaders accountable. And it gives us a framework to take part in public participation.

And once we started doing more of it over the last two years, we realized, actually, we need to change how this public participation is done to include more communities, just referencing what you spoke about earlier. But we would not have known as citizens if we also were not active and took a more passive role. And so, I completely agree with you on that. When we talk about regional institutions, you’ve spoken to the AU, but do you see there being more of a role they need to take in holding their member states more accountable when we can see erosion of democracy happening, or what more do you think they need to do?

Dr. Chukwuemeka Eze:

Part of the work I am leading at the Open Society Foundation today aims to advance regional laws and policies that promotes democratic governance, and making sure that citizens voices are at the center of that process. We are supporting civic actors, but also supporting African Union — ECOWAS, ECOSOC — and some of these citizens fora pushing for citizens-focused politics and policies reform in the Africa Peer Review mechanism, and the strengthening of civic oversight of elections and governance frameworks at the regional level. So, we are working with critical actors to strengthen these regional institutions and amplifying citizens’ demand for dignity, rights, and accountability. So, as a result, we are working in places facing real democratic challenges like the Sahel and the Horn of Africa. We are supporting a coalition of civil society groups investing in new leadership, and working with regional bodies to push for reforms like term limits, political party accountability, and more inclusive participation.

We are also partnering with the UNDP and African Union, and supporting the Africa Facility to support inclusive transitions in countries like Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso to return to constitutional democracy. Our intention is — how do we create spaces for young people and women to share peace negotiations, political future, not just as observers but as leaders? And I believe that to truly safeguard democracy, these regional institutions like AU and the rest need more than just good intentions.

They must be adequately resourced and politically empowered to respond to the continent’s evolving challenges and implement their own standards. However, most importantly, member states must recommit to the spirit of collective responsibility. Supranational institutions can only be as strong as the political leadership behind them. And without genuine cooperation and alignment between national and regional actors. The promise of continental unity will remain a dream.

The longer we defend integration and unity, the more we risk fragmentation, instability, and the erosion of Africa’s democratic goals and decreasing influence on the continent and globally. So, I know that our politicians understand that when they want to engage in bad behaviors at home, the first thing they do is to weaken either regional economic communities or the continental body, and hide under sovereignty. But I think that part of what the citizens must ensure is that democracy in Kenya can only be sustained if democracy in Ghana is functional. So long as any part of Africa is under authoritarian regime, or engage in illiberalism, and all that which is against open society values, Africa’s democracy is still fragile.

Adelle Onyango:

That is such a key point, Dr. Eze, and we’re seeing it now even with the same demographic you’re talking about — the African youth. When they are banding together to hold governments accountable, they’re actually, in a very, almost natural way, supporting that oppression in Togo, oppression in Kenya, oppression in Ghana is interlinked. So, they have already figured that out. I think that’s such an important point to note. And I have to commend the work you’re doing in terms of reforming regional laws because that will really help with holding states accountable. As you’ve said, they hide behind sovereignty, but they have to be held accountable, even by regional institutions.

Dr. Chukwuemeka Eze:

Why do we expect more from our multilateral institutions, we also need to know that old normative frameworks can no longer apply to today’s challenges.

Adelle Onyango:

So, there has to be reforms there as well.

Dr. Chukwuemeka Eze:

I’m not sure what else is reform. I think it’s overhaul.

Adelle Onyango:

Perhaps. Thank you, Dr. Eze, for sharing your insights and for the work that you’re doing because it’s really important.

Dr. Chukwuemeka Eze:

Thank you.

Adelle Onyango:

Now, let’s get into the importance of engaging young Africans in global finance discussions. Let’s hear from Chido.

Chido Cleopatra Mpemba — first, I have to say welcome before I talk about the incredible stuff that you’ve done. It’s such an honor to have this conversation with you and to have you on the podcast.

Chido Mpemba:

Thank you so much.

Adelle Onyango:

You have made history as the youngest senior official in the history of the African Union. And this was as the Youth Envoy, where you assisted in championing youth development issues in Africa, which is incredible work. But I also do have to congratulate you, I’m a couple of weeks late, but congratulations on being an Advisor to the Chairperson of the African Union Commission. And you’re going to be focusing on women, gender, and youth. So, congratulations on this new role as well.

Chido Mpemba:

Thank you.

Adelle Onyango:

When we talk about issues around global financing, I think what I find, which is a common misconception that maybe we can start off by unpacking, is that young Africans don’t engage with issues around global financing, or they don’t have expectations. I don’t think this is true, but maybe we could unpack that with you. What do you think young Africans expect from global financing?

Chido Mpemba:

I think, first of all, we need to touch on the fact that the youngest demographic that we have on the continent are the young people. So, whatever decision or whatever influence that’s going to happen in Africa, it’s going to affect this largest demographic. As a result, young people are interested in every single topic that has to do with their development. We’ve seen that there’s a rise in high unemployment. We see that there’s a lot of conflict across the continent. And this usually affects young people. So, it’s important that, as a result of this, whatever financing architecture is in place is able to go and address such issues that ultimately then impact the young people on the continent.

Now, another thing is this misconception that young people are not really interested in global finance and in architecture. But to be honest, I don’t really necessarily think that it’s because they’re not interested. At times, it’s also because they do not have the knowledge. We all know that knowledge is power. You can only tap into something when you know what it is about and you actually have the knowledge. So, it’s now upon ourselves as different organizations — intergovernmental organizations, multilateral institutions, governance, and even civil society that work with these multilateral institutions — to ensure that the information is out there and young people are aware on what is happening in this multilateral space, what is happening in global financial architecture, and how exactly they can also tap into that. And also go down to education.

When you talk about education, access to education is not enough. We need access to quality education, and education that actually speaks about the current affairs. How do we ensure that we have that education, including in Africa, where young person, as early as being in primary school, is actually aware and is engaged on the global financial architecture and its systems? A lot of people know about the UN, the SDG goals, but I think it’s also important that we speak about the African Union and Agenda 2063, which also is a nexus on the SDG goals, and also looking into these history. Because when you look at the history that most of the young people even learn at schools — not necessarily having to do with development or where we’ve come as Africa in terms of our own development and financial architecture.

Adelle Onyango:

I actually remember being in Addis for the launch of the Youth Chapter of Agenda 2063, and just coming from a media background, talking about how do we break down these issues in a way that young Africans get to touch all of these issues, if we’re talking about global financing, that affects them. And so I’m going to throw into your answer the media as well. The way we talk about the contracts our countries get into has to be in a way that the youth can understand exactly what this means, and not in a way that is excluding them.

Now, I think we can’t, especially when I talk about global financing, we can’t ignore conversations that have been had from before, and even currently when it comes to our African leaders, who are of an older generation, getting very fair criticism for the financing contracts they get into that a lot of Africans feel are quite exploitative and don’t put Africa on the same value level as where the financing is coming from, or lock African countries into debt. And so, I think, in that model, I’m always wondering how we can get more African youth at the tables designing and shaping what these financing models look like.

So, when Africa goes to those negotiation tables, it’s not a begging situation, but it’s a situation that comes with both parties giving value. But I think we can only do that if we have African youth involved. I don’t know what your thoughts are on how we get more African youth involved in shaping these partnerships.

Chido Mpemba:

I totally agree with you. I think it also has to do with our policies, our African policies — how inclusive are our policies towards young people being on the table? We need to start with that. How can we advocate and engage, including with our African Member States, to ensure that in whatever meeting is being held, it’s inclusive of the young people being on the table. The innovative young people. Let’s not forget because the people of quite innovative. Number two, we also need to ensure that when we come to the table as young people, they need to know that we are professionals. We’re coming on the table as professionals.

It’s often such a misconception that young people are often volunteers or we’re doing a voluntary work on the sidelines or we’re doing our advocacy guidelines, but we’re actually professionals interested in the development of our continent. And if you think about it, in the next 20 or 30 years, we’ll be the ones in those decision-making tables, and the generation that’s going to come up to us is going to hold us responsible and accountable for that. So, it’s very important that if it means we’re going to have to bulldoze a way, to say, “Look, we are, and we mean business, and we’re coming as professionals to contribute to the development of our continent because the years to come…” especially when you sit in most of the room, the decision making table, you find that there’s a need for intergeneration leadership or transition of leadership.

How do you ensure that even those that have come before us, they have the knowledge, they have the history, they know what’s going on? And then we are coming in as the younger generation, we have our experience. You know, young people have been very resilient. We face it all — from conflict to high unemployment, just to name a few. So, we are coming with that exposure, that experience, and that innovation. But how do we ensure that there’s intergenerational core leadership? Because we’re not necessarily saying that we do not want the older generation on the table, we do not want them as leaders — but what we are saying is, how can we ensure that we’re able to get on the table together and have a wealth of knowledge coming from both ends, the younger generation and the older generation, and making it work out for our benefit?

Culture is also quite important. When we come to the table, the older generation needs to see that we are also here as professionals. And, as much as our African culture always calls us to be very respectful in the way we approach situations — that, yes, we are cognizant of that culture that we have as Africans, but at the same time, they do not get in the way of business and of professionalism, and also of us being taken seriously.

Adelle Onyango:

You know what? I hadn’t actually thought about it until you mentioned it, where a lot of, in terms of our policies, a lot of young people are sidelined to be volunteers, and it’s almost something you do as you wait for the thing you’re going to focus on, yet the organizations that you’re volunteering in are having such a huge impact on your life in general. And you know what? It’s quite interesting because young people do get involved in global financing, unfortunately, at the tail end when it comes to debt. So, for example, in Kenya, I remember just understanding the math of how much debt I, as a singular Kenyan, would owe, I think I was in my early 20s, for financing partnerships that were drawn up without my knowledge.

So, you are involved already. And so it’s like, how do we get you involved in like the structure? So, I agree with you. The policies and intergenerational approaches to it is really, really important. I would love to know, with your rich experience, have you encountered partnerships that you’re already seeing to impact African communities positively? Because maybe then we can borrow from frameworks that are already working.

Chido Mpemba:

In my role as the Special Envoy on Youth, I had the opportunity to work with a lot of organizations — be it financial institutions, be it multilateral organizations, be it civil society. And there are so many, so many examples of what can happen when we come together collectively. I’ll give one specific example, for instance, now a partnership with the UN Foundation and the Initiative of the Panel of the Future. Again, this specific initiative was on the Nexus of Agenda 2063 and the UN Sustainable Development Goals.

And also looking at it in the context of the Summit of the Future. How do we get more young voices, African voices on the table, and to have an understanding on how this is going to affect Africa for the future?

That conversation and that partnership was very crucial in that it was bringing the young people themselves on the table. At the same time, we had the multilateral institutions on the table, and then we had Africa, including Agenda 2063, on the table. But at the same time, that often needs funding and financing. So, where also have that opportunity to have that interest coming in from a developmental organization to say, “We’re looking to support and to fund this conversation just to make sure that it’s a mainstreamed conversation.”

But I also want to speak with another one, and this speaks more practically in terms of the impact that’s going down to individuals in countries across Africa. And one of them is a campaign that I was able to initiate in my role as a Special Envoy Youth for the African Union, and we call this the Make Africa Digital Campaign. The MAD Campaign. And the MAD Campaign was actually based on, number one, I went on a listening tour, when I became Youth Envoy, I went on a 60 day listening tour just to hear from young people and how they want to be represented, what are the issues that they’re faced with, and ultimately have that as a guide to the priority areas I was going to focus on in my role as the youth envoy.

And one of them was on digital transformation and innovation. As a result, we came up with a Make Africa Digital campaign, and we’re partnered with Google. And so far, we actually trained over 4,000 young people in nine countries through this initiative, where we train young people on digital literacy, literally, because this is where the future is going to. So. how do you ensure that young people are literate enough when it comes of the transformation of technology? But second to that, I then realized that inasmuch as we are training young people, not everyone has access to technology in Africa.

This is access to the technology, and even access to internet or affordable internet. I remember when we went to Ghana and we went to a village that’s just far off from Accra, and we were there and getting ready to train these young women in this village on digital literacy, and they’re saying, “First of all, just the access to a computer is very difficult in this community, and even the digital infrastructure.” So, I thought it’s also important in that case that, inasmuch as, yes, you’re working with this institution or working with Google on the aspect of training young people, but access is also equally important. And that also often means that we need to work with the member states. Agreeing to work with the member states, policymakers to open up this space in terms of internet affordability, in terms of infrastructure across the whole continent.

Thirdly, in the end, we actually developed a policy brief. And I launched this policy brief from the margins of the UN General Assembly last year in 2024 because once we’re doing the digital literacy trainings, we also would then convene consultations on the margins to say these are the issues and people are faced with. And ultimately, we put that in the policy brief to share with our member states. And this policy brief also focus on artificial intelligence, to say sustainable development and youth in Africa, and in terms of artificial intelligence, what needs to be done and what can be done, and how can this guide future financing?

Because it’s important that when you talk about financing, having access to financing, we should have done the research as well. We should have the knowledge on the ground and be able to show the evidence that these are the issues on the ground, and this is how you can address them. So, as a result, this is where the money can be put for the impact.

Adelle Onyango:

I want us to go back to the listening tour because I think so many leaders or potential leaders listening could learn from that. What does a listening tour look like? Because I think a lot of times, that step is missed.

Chido Mpemba:

For me, a listening towards being intentional and also be open to learning. Because when you’re going on the ground, yes, I might be coming from the African Union, or I might, at the time, have been appointed as a Special Envoy in Youth, but it doesn’t mean I know everything. I can learn so much from others in being on the ground, especially the people that I represent. So, it was very fulfilling, and it was such an eye-opener. And, actually, I had a model, an engagement model for the listening tour, so would actually start with a youth townhall meeting, would convene different stakeholders with youth townhall meeting.

And the second part of the model was community engagement. The community engagements literally go down to the communities, to the villages — sit down, talk to young people, talk to young women, get to understand, document as well, document their voices, how they want to be represented. And at the end, it’ll be political engagement. Because I said, since I have the seat that I’ve been given an honor and a privilege on the table, how do I make sure that, because of that seat and the access that has been provided, we make the most of it for young people?

So, I’d make sure, in every country that a visit, I would end with the policy and political engagement — be it, in some instances, those actually adhere to state level or ministerial level, but you actually sit down and say, “Look, I was in your country. This is what I discussed. This is what I saw on the ground. This is what I’m advocating for for the African Union. But at national level, because not one size fits all, this is what we hope for you to be able to do.”

Adelle Onyango:

Thank you, Chido, for the work that you do and the gems that you dropped for us today.

Chido Mpemba:

Thank you so much. It’s just been such an honor engaging with you.

Adelle Onyango:

Last but not least, let’s listen to how the creative economy can help place Africa on that global stage with Jake.

Jake, thank you for joining us on this podcast.

Jake Bediako:

I’m really excited to be here.

Adelle Onyango:

I would love to know your insights. Also, based on just your experience working and advising governments in Ghana, why should African governments leverage youth involvement in their policies? So, let’s start with the why before we pick your brain about the how.

Jake Bediako:

Africa is home to 70% of young people. Africa is 70% young people. And so, it’s not even a suggestion as to why governments should include… This is 70% of your population we’re dealing with. So, there’s really no excuse. The electorates, your taxpaying citizens, 70% of those people are young people. And so, it’s not really optional. But even more so, I think we’ve moved from the point on our continent and in the world, where young people are only leveraged for their energy. And now we need to get to the point where young people are in the driver’s seat of the world that they seek to inherit.

It’s not enough to have young people at the core of your mission, or your manifesto, or your policies. You actually have to involve them in it. Well, the initiatives that I helped drive was this initiative called Youth at the Table. It’s a mentorship conference to prepare young people for the decision-making tables of their various countries. And it’s drawing on the expertise of people who are much older to say, “Okay, how do we get where you are faster?” And that is extremely important because it’s not enough to wait anymore. There’s a book I read called The Bright Continent, and it was talking about a phenomenon in Africa where we have childhood waithood and then adulthood. Most people transition from childhood to adulthood.

But in Africa, it seems like over the decades, we’ve had this period in a young person’s life called waithood. And waithood is a waste of energy, is inefficient, and it is holding us back to develop mentally. And this is why it’s important that youth representation in government at decision-making tables is prioritized because it’s not enough, like I said, to just have policies that consider young people. It’s extremely important to have young people designing these policies. And so, the position I found myself in at age 27 when I started working in the government was fantastic for me, but it was not enough.

There should have been more of me at the decision-making table. I would be in a minority in so many rooms, advocating for things young people cared about. Because, obviously, I had to juggle that with the interests of other older groups while bearing in mind that we are 70% of the population. So, our concerns and our needs actually should be paramount. This is not for any government to overlook. And some governments have made strides. I mean, there was, at the time, I was youth advisor. There were two other youth advisors on the continent, and I think another country took on a youth advisor. So, Namibia started, Ghana followed, Uganda was also in the mix as well.

And then I think Botswana also added a youth advisor. But all that time we also then had the AU bring in the AU Youth Envoy, which also pushed the youth agenda. But the youth agenda in Africa is extremely critical to our development, and so it’s not something to be overlooked.

Adelle Onyango:

I’m 36 now. I feel like I have experienced waithood since I was in primary school because you’re kind of seeing the same leader saying, “Youth, your future is tomorrow. You’re the future of this country.” And they’ve been saying it across decades, and it’s like, how can we inject more young, fresh energies at the steering of agenda driving, policy driving? You’ve given one example, but I wonder if you have more. Some of the structures or projects or ways that you saw that you could help, though, wasn’t purely performative, because maybe that can inform youth advisor structures in other African countries.

Jake Bediako:

Structures are not only governmental. There are social structures at play as well. Being appointed by a forward-thinking president is not enough. You need the machinery behind you. And that is where the difficulty comes in, because, culturally, it’s difficult for people to take you seriously as a young person at that level because you’re the easiest person to pick on, because you’re a young person. There are so many barriers to young people engaging in this. So, it’s not even about being performative as much as it’s we as a society, we as a country, say we want this. We want young people to step up. We want to hold these things.

Our systems, our cultures, our societies do not support the growth of young people in these spaces. Young people, especially young women, go through this a lot because you see that a young woman steps into a space and takes authority, and speaking truth to power and trying to influence policies, and the response is usually not anything productive towards her. It’s this critique. It this telling her she should be a good girl. A lot of things that minimize the young people and the role that they can play. The policy around it can be fantastic. There can be leadership support for it.

But at the end of the day, I always say, even if you are appointed by a head of an organization, you have to work with the people within the organization. So, the organizational culture, the national culture, and for me, working on a governmental level, national culture is also important to take into consideration because that’s what you’re actually up against every day. It’s not even within. It is the people within the structures that be, and also the wider population. So if Africa is serious about young people in positions of power, we are going to need a societal communal overhaul of how we even think about young people and our capabilities.

Adelle Onyango:

That is so on point. I have a young African friend, a Kenyan woman who ran for office a couple of elections ago. She was campaigning in the community where she grew up in. Her family had lived there. She had a deep understanding of their issues. And, as the election grew closer, she was summoned by the elders, who are like a group of older men. And some of the questions they said is like, “You are our daughter’s age. How can we look towards you for instructions or direction?” And that really speaks to social structures, because I think sometimes we only think about the framework that you’re working within and not really the people you’re working with.

Jake Bediako:

And that exacerbates the waithood that I was talking about because these older men probably have their children in waithood, so they cannot understand that somebody has moved out of that into full-on adulthood and into leadership and into becoming the peer or even becoming their leader. So, it’s a lot to deal with. But that’s where the change needs to happen. Because we can have all the policies — Without that social change, it will be difficult to implement.

Adelle Onyango:

And when we look at forums like the African Union, what do you think they need to do more of in this bid to ensure that Africa’s influence is felt as an innovator, as a global leader? At least I know, for us in Kenya, they come under a lot of heat when people want them to do more and arrive more. What do you think they need to do more of?

Jake Bediako:

I think the African Union is undergoing a renaissance because Africa is a bright light at the moment. It has always been, but now the world recognizes our brilliance. And I think the African Union is recognizing that this is the time to leverage, and the time to leverage young people. If you’re following the journey of Chido Mpemba, who was the AU Youth Envoy, and is now the Advisor to the Chairperson on Women, Gender, and Youth, we are seeing the seriousness being brought to the conversation. And leveraging young people is a very important thing to do if the EU is really going to see the light of the future and the light of day, right?

Because the work that they’ve been doing has been flying under the radar. But I think a lot of us have started paying attention when we started seeing the youth engagement component to what they’ve been doing. Or maybe we just biased, and because we are young people, we are looking. But then, for me, I see a real opportunity for the AU to further its reach and to almost make themselves a household name through the engagement with young people.

Adelle Onyango:

Something that I’ve seen even the AU do really well is like tapping into the creative economy and into the arts. Let’s actually break down the arts, because I think the arts have such power in uniting people and sparking connection and even giving hope, because where Africa has come from, hope is like a key ingredient to get to that global stage, right?

Jake Bediako:

Yes, absolutely.

Adelle Onyango:

And so with the work that you do, I just want to pick your brain about the role the creative economy plays and the arts in uniting and building the Africa that we all want to see on a global stage.

Jake Bediako:

That is the most important thing to me at this time. Obviously, I’m biased because this is what I do, and it’s very important work. It’s the way to scale the impact of Africa in the world, the fastest. Because, like, we keep going back to this 70% youth population thing — who are the custodians of Africa’s creative sector, Africa’s creative growth? Who are the people that brought Africa to the world? It wasn’t the older people. It was actually young people who control the culture that took it to the next level. And so, it’s really important that we empower young people to do that. If you want to impact young people on the continent, it is the one foolproof way to impact the most young people across different social stratification, across different skills and interests and business levels, whether they want to be business owners or freelancers, everything in between, or they want to be full-time employees.

The creative sector is the easiest way to target young people on the continent. And so, if we want to do that, we have to create those global opportunities and those global standard opportunities to give them opportunity, right? So, to give them the impact that they need to have.

Adelle Onyango:

What would we need to change in terms of the social structures to allow the creative economy to propel us to the next level?

Jake Bediako:

We just need to show what’s possible. We need to show the scale and the magnitude and talk about the real impact that this can have. The creative sector is a multibillion-dollar sector. It’s not a sector to be played with. But then we are so focused on the traditional sectors of yesteryear, which have stabilized. But in terms of bringing growth and opportunity, the creative sector is the biggest, if not one of the biggest if I’m being conservative, but, in my opinion, is the biggest way, and the fastest way, the most effective and efficient way to scale opportunities on the continent.

Because you see, we look at it as — or maybe a performer will make money or an artist, and I’ll bring a little something. No, it is down to the person designing the stage, the person rigging, an architect who will do the floor plan. It’s everybody. It’s a sector that is also available and open to everybody. So, it’s really important that we look into it as a real sustainable sector in which we can create opportunities not just for our dubbed creatives, but people who have other skills but also have an interest in the creative sector.

Adelle Onyango:

And you know there is a ripple effect as well. Like, if you’re talking about that level of concerts happening, it’s also going to positively impact the tourism industry. If we’re talking about accommodation, if we’re talking about transport, if we’re talking about… Industries that may not even directly be part of the creative economy get impacted positively. What do you think is the role of the African diaspora in ensuring we’re holding up our continent on this global stage?

Jake Bediako:

The role of the African diaspora cannot be understated. We are a continent whose people were stolen from us. And for that reason, we are having to develop with less than our full capacity of human resource that was available to us. And so, coming home to the continent of Africans in the diaspora, whether it’s to Ghana or to Nigeria or to Kenya, or wherever, it’s actually a pooling of our resources. It’s the reversal of the brain drain that didn’t just start in the ’90s or the ’80s, but actually started 400 years ago. And so, what we are up against is pooling our resources back together so we can develop this continent. And so, the diaspora has to be involved. And this is why the AU has called the diaspora the 6th region, right?

Adelle Onyango:

Yeah.

Jake Bediako:

Because it is part of our constituency. We cannot do it without the diaspora, not because we on the continent are not working hard enough — no, no, no, no, no. And not because we don’t have what it takes. No, not at all. But there is a skills transfer and a knowledge transfer that is needed to be able to scale up. We’ve been out away building other countries that are now benefiting from the impact of having had where there was forced labor or immigrant labor. And now, it is Africa’s turn to benefit from that demographic and from that population that we have not had at our disposal for various reasons.

Adelle Onyango:

What do you think is the next smallest step? Because one thing that you say that I truly agree with is that there’s a responsibility for all of us.

Jake Bediako:

It’s about organizing and making those small personal decisions, whether it’s to wear African brands and promote them. It is also just advocating for African-related things in your workplace, or wherever you have influence, advocating for Africa. That is what is going to make it reverberate. There was not a concerted decision that Afrobeats would take over the world in this way. There were people working hard at it, but everybody that loved it put their hands to the plow, and that’s why we find ourselves where we are. We couldn’t have imagined Afrobeats being played in mainstream clubs in New York and London. That was unheard of when I was in university, and that was not even that long ago. And it’s those little actions that we all take in our workplaces, advocating for more African representation, or more policy work done in Africa, or more engagements with…

However, you can use your sphere of influence to promote Africa, you do that. and that is what is going to actually move the conversation forward.

Adelle Onyango:

Your insights on this podcast are very, very valuable. So, we thank you for making time for us.

Jake Bediako:

Thank you so much for having me.

Mark Leon Goldberg:

Adelle, that was such a great episode, and a great debut to the series that I am really excited about.

Adelle Onyango:

Exactly. It really puts it to, at the core, what we’re trying to talk about in various aspects that Africa needs to take its place on the global stage.

Mark Leon Goldberg:

So, that was episode one of what will be a seven-episode series that we are releasing now through September. Some of the topics we cover include climate peace and security, partnerships and financing for development, how to close that trust deficit between people and their government, education and the future of work in Africa, the unique role of women in Africa’s rise, and how to tackle some of the continent’s most urgent health problems.

So, that is a lot to cover over the next few weeks. And Adelle, I know we are deep in the production process right now. What are you most excited about?

Adelle Onyango:

I think I’m excited about hearing solutions that are working in different African countries that the rest of the world can borrow.

Mark Leon Goldberg:

As I said, I am really excited for the rest of this series, and listeners, you are in for a treat. This is such a great debut episode, and I’m so excited for what we have in store over the coming months in the Future of Africa Podcast series. So, thanks so much, Adelle, and we’ll see you after the end of the next episode.

Adelle Onyango:

Thanks, Mark. Looking forward to the next episodes. And this, as you’ve said, has been a brilliant beginning, so there’s more to come.

Mark Leon Goldberg:

Thank you for listening to The Future of Africa — a special series on Global Dispatches produced in partnership with the African Union, The Elders, and the United Nations Foundation. I’m Mark Leon Goldberg, the host and founder of Global Dispatches. This series is hosted by Adelle Onyango. It is edited and mixed by Levi Sharpe. You can find all episodes in this series and access episode transcripts at globaldispatches.org.