When Treaties Work: The Chemical Weapons Convention

The inside story of a wildly successful treaty

A happy New Year to you all!

Alas, I fear 2025 is poised to be a year of profound upheaval in international relations. Trump 2.0 may usher a new era of geopolitics in which the United States will pursue a foreign policy premised on a narrow and short-sighted interpretation of national interest, and in the process alienate traditional allies and potentially break from many of its historic multilateral commitments.

As we enter this new era, the very idea of international cooperation to solve global problems may come under attack. But it is a principle worth defending.

The Power of Internationalism

At its core, “internationalism” is the belief that the world can become a more peaceful, prosperous, and sustainable place when countries work together. It acknowledges that certain global problems—like pandemics, extreme poverty, climate change, and the threat of war—can only be addressed through collective action.

Having spent twenty years reporting on foreign policy and international affairs, with a focus on the United Nations, international law, and multilateralism, I’ve seen how international cooperation can lead to progress. While sometimes imperfect or incremental, these efforts drive meaningful advancement toward the global good.

This might sound idealistic, but the truth is: Internationalism has delivered tangible results. These range from the mundane (you know how much postage to use when sending a letter across borders thanks to the Universal Postal Union), to the uplifting: diseases like smallpox have been eradicated, and polio is on the brink of eradication; to the existential: there were two world wars in the decades preceding the advent of the United Nations, but none since.

One manifestation of this progress are treaties: the mechanism by which countries agree to legally bind themselves to take certain actions and in the process create new international law. Today, I’m proud to announce a new content partnership between Global Dispatches and Lex International around a series that showcases how treaties have worked to positively shape state behavior. We are calling this series “When Treaties Work” and I could think of no better treaty with which to debut this series than the Chemical Weapons Convention.

The Chemical Weapons Convention Works

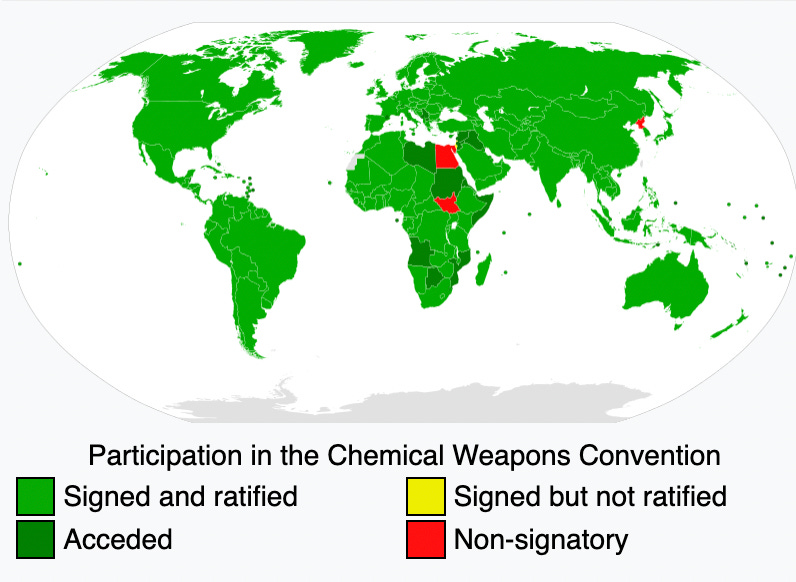

The Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC) prohibits the manufacture, stockpiling, and use of chemical weapons. It entered into force in 1997 and has since become the most widely adopted international arms control treaty, with 193 states parties.

Since its adoption, every country in the world has destroyed its declared stockpiles, including, most recently, the United States last year. Furthermore, its widespread acceptance has strengthened international norms against the use of chemical weapons in warfare. When chemical weapons were used in Syria in 2013, the mass atrocity so shocked the world that both Russia and the United States pressured the Assad regime to join the CWC. This allowed investigators from the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) access to Syria to assess and facilitate the destruction of its remaining stockpile—an effort that earned the OPCW the Nobel Peace Prize later that year.

The CWC is fulfilling its intended purpose. Joining me to explain how and why the CWC was created, how it has achieved such success in influencing state behavior regarding chemical weapons, and what comes next for the CWC now that all declared stockpiles have been successfully destroyed, is Paul Walker. He is the chair of the Chemical Weapons Convention Coalition, Vice Chair of the Arms Control Association, and a former weapons inspector. We kick off by discussing the history of efforts to ban the use and production of chemical weapons before delving into a broader conversation about how the CWC has forever changed the world’s approach to this weapon of mass destruction.

This episode is freely available on all podcast platforms, including Spotify and Apple Podcasts. The transcript is available here.

Transcript edited for clarity

Mark Leon Goldberg: So, Paul, thank you so much for joining me. Just to kick off, I would love to have you address the big picture question of what distinguishes the Chemical Weapons Convention as an international treaty.

Paul Walker: As a treaty, it’s the most universal of all arms control treaties in the world. It has 193 state parties, second only to the United Nations. There are four countries still outstanding from the treaty for a total of 197 countries. But the number of countries is changeable every year. Secondly, it has abolished one of the most deadly and inhumane and non-discriminatory weapons available other than nuclear and biological weapons. It abolishes horrible weapons that we’ve seen in the past wars. So, it’s a real historic breakthrough to have so many countries, really the whole world, something like 99% of the world population adhere to the treaty.

Mark Leon Goldberg: And, I mean, that is a remarkable number, 193 member states. What are the outliers?

Paul Walker: There are four outliers. One is South Sudan. We’re patiently waiting for South Sudan to accede to the treaty. It has said that it wants to accede to the treaty, but as a brand-new country is rather slow in joining treaties. Egypt and Israel as well. Egypt says it won’t sign or ratify due to Israel’s outlier status. And Israel has signed but won’t ratify. The Knesset in Jerusalem has not ratified any arms control treaty. Egypt and Israel are thought to have stockpiles of chemical weapons. And the fourth country is North Korea. And North Korea doesn’t communicate at all with the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons, the implementing agency of the Chemical Weapons Convention. The expectations are that it’ll be a long time before North Korea accedes. And then we also have Taiwan. And Taiwan is not a member of any international treaty due to the one-China policy of China. But we hope that, in some fashion, it can be at least inspected, if not a member of the treaty in the near future, given the large nature of its chemical industry.

Mark Leon Goldberg: So, I mean, just the global reach of this treaty is really remarkable, as you said. There are just very scant number of outliers. Can I have you just take us back in time, and can you describe, what is it about chemical weapons that make them a particular category of weapons? That is something around which so many countries around the world, so many governments around the world have sought to abolish.

Paul Walker: It’s historically just the horror of using chemical weapons. I mean, a little over a hundred years ago, it was April 1915, when the Germans released chlorine gas at Ypres, Belgium. It was the first time where gas had been used on a massive level. There were 5,700 canisters. It wasn’t weaponized. It was gas canisters released by the Germans when the winds were behind their back. And it killed the maimed thousands of allied forces opposed to the German onslaught. And by the end of the war, something like a million troops had been injured and over a hundred thousand killed, I think. So World War I was really the turning point. We went into the Geneva Convention in 1925 and banned the use of chemical weapons and biological weapons too. It had also been raised in The Hague treaties of 1899 and 1905. But the turning point was really the Geneva Conventions.

Audio Excerpt: 20 years of talking about how best to get rid of chemical weapons altogether came to fruition in Paris, January 1993. It was here that an agreement was signed that not only banned the use of chemical weapons, but also their development, production, ownership acquisition, and sale. This agreement reached at the conference on disarmament in Geneva the previous year was more far-reaching than many of its supporters had dared to hope for.

Paul Walker: Unfortunately, the Geneva Convention banned the use, but it didn’t ban anything else. Didn’t ban research development, testing, production, storage, and buildup of stockpiles.

Audio Excerpt: This is the research center of the technical command at Edgewood Arsenal, Maryland. It is the largest laboratory and coordinates the research carried out at other laboratories. And these laboratories have been found and the engineering work done on our war gasses and the weapons to project them. Samples of gases captured from the Japs in the South Pacific and samples procured from Germany by secret agents have also been analyzed here.

Paul Walker: So, all the major warring powers went forward in the development of chemical weapons. We saw a little bit of chemical weapons used. I say a little bit. There’s still horrible killings — Japanese against the Chinese.

Audio Excerpt: China has held a photo exhibition of chemical weapons left behind by the imperial Japanese army during its invasion to the country over 80 years ago.

Paul Walker: We had uses in Yemen, we had uses in Ethiopia. But the real problem became when Iran-Iraq, in the 1980s, had an eight-year war. And we saw, once again, Saddam Hussein really use chemical weapons on a massive scale against his own people, but also against the Iranians.

Audio Excerpt: When they bombed us, nothing happened. We had no problem. But after almost four hours, my body started reacting to the chemicals. First, my eyes started to burn and then I started vomiting badly. I felt like I was dying. And my skin started to blister on my eyelids around my mouth, neck, and anywhere else that was wet.

Audio Excerpt: Zangiabadi, like so many other Iranians, signed up to fight after Iraq invaded Iran in 1980. But he was gassed during Iraq’s first major chemical weapons attack four years later. According to its own declarations, Iraq used more than 101,000 chemical bombs and munitions during 80 years of war, including mustard gas and nerve agents.

Paul Walker: That led all the more towards the diplomats to negotiate a treaty. I think also, historically, you find that chemical weapons really lost their military use. Most of the powers that developed large stockpiles, particularly the Soviet Union and the United States, really found no particular military use, and they became troublesome to actually maintain. They leaked a lot. They wounded or killed a few troops in various countries.

Mark Leon Goldberg: Is the limited military utility of chemical weapons a consequence of the fact that they’re inherently indiscriminate?

Paul Walker: Yes, I think so. And it also is connected to the fact many of us had nuclear weapons too. And compared to nuclear weapons, chemical weapons weren’t very helpful. Although, I’ll tell you, when I was in Russia 20 years ago and we were demilitarizing the Russian stockpiles, I had several Russian generals say to me, “You Americans are simply taking these chemical weapons away. They’re a definite step on the escalatory ladder before we get to nuclear weapons.” And they want to retain their chemical weapons. That was a minority. Minority of the military in Russia, and it was probably a minority of the military here in the United States. I think most countries never researched chemical weapons. It didn’t have chemical weapons.

And when push came to shove and they had to declare them to the treaty in the 1990s, only eight countries declared stockpiles. We had had at least 40 or 45 countries invest in research and development, but they all, by the time of the treaty in 1993 when it was open for signature, most had destroyed their stockpiles in some fashion.

Mark Leon Goldberg: Well, what was the political impetus to begin negotiations on a treaty to ban the use of chemical weapons and also the production of chemical weapons? I mean, it sounds, as you’re saying, a lot of it was derived, at least in part, from the horrors of seeing them used at least more recently at the time during the Iran-Iraq war. What and who was responsible for the initial development of this treaty?

Paul Walker: Well, the Americans and the Soviets began negotiations in the 1980s bilaterally to eliminate their stockpiles. Neither country wanted chemical weapons. They both had enormous amounts. Russians had declared 40,000 metric tons. The Americans declared 28,600 metric tons, and they wanted to get rid of them. So, there was an agreement called the Wyoming Agreement that was signed back in the late ’80s to get rid of them. That was outside of the negotiations going on in Geneva for the Chemical Weapons Convention. The Geneva negotiations begun, I think, by the British and other countries went on for over 12 years in the Conference on Disablement. But they finally came to agreement. There were a lot of disagreements over verification, inspections, declarations, what was actually covered. Are you going to cover research and development testing?

In the end, the treaty bans everything you can think of, basically, but research. It allows limited research, and that goes on today in many countries. But there’s no development, production testing, deployment, or use allowed. It’s a wide range. It bans deadly chemical weapons, highly toxic chemical weapons. But the schedules, which list the chemical weapons as appendices to the treaty, also ban riot control agents, RCAs, which we think now Russia are being used by the Russians in Ukraine.

Audio Excerpt: the chemical weapons against Ukraine, and therefore violating the Chemical Weapons Ban. In a statement on Wednesday, the U.S. State Department said it had made a determination that Russia had used the chemical weapon, chloropicrin, against Ukrainian forces in violation of the Chemical Weapons Convention, or CWC, and that Russia also used tear gas during the war, which is also in violation of the CWC.

Mark Leon Goldberg: So, you said that it really was the result initially of bilateral negotiations between the United States and Russia, the two countries with the largest stockpiles, that led to the Chemical Weapons Convention. But yeah, the CWC wasn’t open for signing until after the fall of the Soviet Union in 1993. To what extent does the fall of the Soviet Union almost precipitate momentum towards a universal adoption of this agreement?

Paul Walker: I think it does indirectly. The Wyoming agreement and the demilitarization of chemical stockpiles was begun by the United States unilaterally in the late 1980s. We had a stockpile on Johnston Atoll, what we call JACADs, in the middle of Pacific Ocean, 800 miles west of Hawaii, where we had stockpiled chemical weapons, we had previously held secretly in Germany and Okinawa. And we built the first prototype incinerator there on the island. The island itself has a long history of with Agent Orange and plutonium and other highly toxic materials. But we began that demilitarization process in 1990 unilaterally. The Russians, to my knowledge, didn’t do anything on technology development or demilitarization until about 1994. And I was part of a unique onsite inspection of a Russian stockpile called Shchuch’ye. It’s the Eastern most stockpile in the Kurgan Oblast of Russia, one of Russian’s seven stockpiles — had 5,400 metric tons of nerve agents.

And we, as an official in inspection team, went in with a couple of congressmen and head of the U.S. Chemical Weapons Program and head of the Russian Chemical Weapons Program, and just saw that these weapons were largely obsolete — No launch systems, no security, no inventory, actually. I think the U.S. was smart enough at that point to realize the Russians had to move forward. And we began helping the Russians under the Cooperative Threat Reduction Program to figure out what to do with… They had no idea how to destroy the weapons at all. First thing we did was we put security on the site. We enhanced it with the fencing and guard towers and guard dogs and video surveillance, electronic surveillance, and the like. But the second thing was we got them going on Technologies of Destruction and offered them an incinerator at the time, same as we were building three or four sites in the United States.

And they refused that. They didn’t want incineration. They thought it was too expensive, too complicated, too dirty, too uncontrollable. And they developed a joint research project and developed neutralization, as we were too in the same case, developing alternatives to incineration as well. So, I think the Soviet shift in ’89, ’90, ’91 to Russia really had a remarkable push forward for the ongoing demilitarization.

Mark Leon Goldberg: I mean, that’s just wild to me that you would have this massive stockpile just sitting there unguarded with no inventory, just like an accident or a disaster seemingly waiting to happen.

Paul Walker: Well, it was under the military, but it was a very remote part of the Kurgan Oblast. It was two-hour drive from any major city. But it had 14 villages surrounding it. The weapons were stockpiled in basic warehouses, corrugated metal with swinging ban doors. It was right on the Kazakhstani border. We were fearful of leakage of weapons. This was July 1994 this onsite inspection was taking place. We asked the local village administrator, hypothetically, if we were interested, could we take a few weapons with us? He sort of looked aside, and then he smiled and he said, “Sure, how much would you pay?” And we didn’t do that by the way. But the risk of proliferation of leakage from these stockpiles was really extreme at that point. And we wrote a classified memo at the time when we went back to Washington, and I was representing the Armed Services Committee and the House of Representatives to which I served a couple years.

We began immediately working on schemes to put high security on that site and one other place called Kizner in Western Russia that both had man portable weapons on them. It was a real danger. But it showed to us that the Russians really didn’t intend to use this stuff at all. That stockpiles gone today, as are all the others. So, it’s been a big success program of cooperative threat reduction and also the Global Partnership Programs of most of the Western allies, many like the Germans and the Brits and the Italians, and others that pitched in and helped fund the Russian program of demilitarization.

Mark Leon Goldberg: Yeah, I mean it seems like it was this unique geopolitical moment that enabled cooperation between Russia and the United States, combined with the fact that these weapons were generally obsolete that led to the opening of the Chemical Weapons Convention for signing in 1993. Could you just walk me through what the Chemical Weapons Convention obliges of countries that have signed and ratified the treaty? What are the key elements of this treaty that are enforced today?

Paul Walker: The most important key, of course, is, and the goal of the treaty is the abolition of chemical weapons stockpile. So, joining the treaty, a state party, a country is obliged to present its initial declaration — declaration consisting of basically a history of anything having to do with chemical weapons. That’s research laboratories, production storage, testing, all the weapons stockpiled throughout the country. It also requires including any weapons testing outside the country. And there have been a number of testing programs outside the United States. We had an old program down in Panama in the San Jose Islands, which was pretty egregious live testing on human beings. It also obliged them to report annually, in a much shorter annual declaration, as to what, if anything, what’s happened in the past year. It obliges countries to report anything going forward in what is allowed under the treaty, and that is research in toxic chemicals.

It also obliges them to engage in inspections. The OPCW, the Organization for the Prohibition can enter a country on short notice and inspect, at any time, suspicious activities. But they have regular industrial inspections too, which are very important. And there are 241 inspections globally of industry and whether they have the potential for production of toxic materials. A lot of these chemicals are also dual use. Like chlorine, mostly industrial, but have toxic properties that they could be used nefariously if wanted to by non-state party or by a state party. So I think the obligations are actually very serious, but it’s led to a world without chemical weapons, except for a few examples, particularly today by Syria and Russia. It also promotes peaceful uses of chemistry. So peaceful uses of chemistry, the availability of technology, of laboratory equipment, and the like is promoted, just as peaceful uses of nuclear energy are promoted through the IAEA, the International Atomic Energy Agency.

Mark Leon Goldberg: What is interesting to me about the Chemical Weapons Convention is that you do have a number of arms control treaties around the world that are of varying degrees of success. Like countries sometimes follow the strictures of a treaty, sometimes don’t. What seems interesting to me is just how well enforced and adopted and embraced this particular treaty is and has become over the years. I do want to talk about the outliers that you mentioned, Syria and Russia. But before we get there, can I have you explain some highlights or discuss some examples of ways in which this treaty has done what it is intended to do when those who crafted it wrote the treaty document itself? What are some of the key highlights of this treaty over the last several years that you would point to, to anyone wondering whether or not this treaty really has had an impact on state behavior?

Paul Walker: There are a lot of highlights. Actually. It’s been a very successful treaty. I think part of it is due to the fact that we’ve had very good director generals, the head of the OPCW. The first Director General, Jose Bustani, got in trouble around Iraq and resigned in 2001, I think. But the three successor Director Generals, Rogelio Pfirter, an Argentinian diplomat, Ahmet Üzümcü, a Turkish diplomat, and the current one, Fernando Arias, have done really an excellent job in running a bureaucracy that’s about 450 people, depending on the size of the Inspectorate. Has a budget of about 85 million euros per year in The Hague. One example would, I think a prominent one would be the final destruction in July of 2023 last year of the American program. We declared seven stockpiles, all of them extremely large except one in bluegrass, Kentucky.

It was a tedious program of trying to destroy the American stockpile of 28,600 metric tons. And it was an ongoing fight here in the United States between technologies of destruction.

Mark Leon Goldberg: Meaning that some groups oppose, say, incineration of these chemical weapons for the fact that weapons it might impact or hurt local communities.

Paul Walker: Yeah.

Mark Leon Goldberg: And so, there was this process of trying to figure out alternate technologies to incinerations that would, I think, allay some of these concerns.

Paul Walker: Incineration, in general, is a big red flag for the environmental and public health communities. And so when I left the Armed Services Committee, I proposed to open up outreach offices and public dialogues at every single site. And in the end, the Americans chose incinerator at five sites and neutralization, a wet chemistry process at four sites is much more controllable than incineration. Rather than having all the atmospheric waste go up the smokestack, you batch control it and maintain control over everything that goes through the process until you know it’s safe, then you can release it to a secondary process. Cost overrun and delays were yearly. And the U.S. Army had first proposed that they would be finished in, unbelievably, in 1994, 4 years after starting it.

And that kept getting extended to 97 and beyond. The treaty set a deadline for declared stockpiles of destruction as 10 years after entry in a force, which is 2007. And nobody met that deadline, unfortunately. But in the end, in the wisdom of the state’s parties and the director general and all the staff at the technical secretariat, every country, eight countries were able to destroy their stockpile safely and soundly. And to the best of my knowledge, nobody was seriously hurt or killed.

Mark Leon Goldberg: So, as of 2023, the United States destroyed its last remaining stockpile. So, all declared stockpiles have now been abolished. However, there was the outlier issue of Syria in 2013, not a member of the Chemical Weapons Convention at the time, but the issue of the use of chemical weapons became internationally prominent once again in the context of the Syria conflict. Can you just take us back to 2013 and explain what we know about Syria’s use of chemical weapons on its own soil against its own people in the context of the Syria Civil War?

Paul Walker: Yeah, it’s a very sorted story of dictatorship using chemical weapons in the Civil War that started in around 2011 — keep his populations under control. He had used chemical weapons in a small way in 2012 and early in 2013. But in August of 2013, he attacked Ghouta, which is a suburb of Damascus to the east, and he killed its estimated 1400, mostly civilians, with sarin nerve agent.

Speaker 9: On August 21st 2013, rockets filled with sarin gas rained down on density populated neighborhoods in eastern and western Ghouta near Damascus. 1,400. Syrians were killed, including hundreds of children, as well as a large number of animals. The UN expressed outrage, and the U.S. threatened intervention. But that didn’t stop Assad from attacking his own citizens many more times.

Paul Walker: He was not a member of the treaty at that point. He was one of a very few outliers. Pressure was put on him by the Russians, who were an active member of the treaty, and the United States. And he acceded to the treaty the next month in September. And he declared, in October, 1308 metric tons of chemical agent and precursor chemicals. But the problem was we couldn’t destroy them in the middle of a civil war. The treaty never envisioned destroying chemical weapons outside the country that declares them. Eventually, as you know, a deal was worked whereby the United States would pick up the chemicals by ship and destroy some of the chemicals onboard, a ship called the Merchant Marine ship called the Cape Ray, and deliver some of the chemicals to Germany and Britain and Finland and the United States to be destroyed in various ways in each of those countries.

And that’s what happened. The chemicals, particularly the precursor chemicals, were not particularly in a good shape. And they had to be prepared still further. It was an expensive operation and it’s a long story as well. We don’t have time for it. But the good news was he gave up, allegedly, all his chemical weapons. Unfortunately, he continued to use chemical weapons, sometimes in rudimentary chlorine-filled barrel bombs, and once in a while in sarin artillery, and the like. ISIS also started using chemical weapons. And the OPCW fortunately went into inspect immediately after the Ghouta attack.

Mark Leon Goldberg: Which killed something like 1300 people. It was the worst chemical weapons attack in the context of a war since World War I.

Paul Walker: Yes, it was, it shocked everybody. But he apparently didn’t give up all his weapons and didn’t declare all the weapons. OPCW Inspector auspices, he destroyed, I think it was 27 storage and production facilities, and he opened up two or three laboratories or more. So, it was a credible initial declaration. But the declaration to the OPCW came up with over 25, 26 big questions. And six or seven of them to date have been resolved, but 19 of them were not resolved. There were inspector samples brought back at certain sites that said certain chemicals we used at that site that he didn’t declare. So, Syria was a real case of a state party going seriously wrong and violating the treaty.

And I think the recent regime change in Syria bodes well for finally getting inspectors in and inspecting what wasn’t declared previously.

Mark Leon Goldberg: Well, I wanted to ask you about that. So, we are speaking in late December, it’s been just a few weeks of this transitional government that’s taking shape in Damascus. So, what opportunities now exist for the OPCW and other members, other interested parties to use the treaty, to harness the treaty that Syria has signed in the context of that pressure campaign by Russia and the United States that you cited in 2013? It seems there is almost a plug-and-play way that the OPCW and other international countries can go in and help Syria destroy its remaining stockpiles, which, again, seems to demonstrate the value of this treaty.

Paul Walker: Yeah, I think you’re right, Mark. I mean, there’s been an executive committee meeting held just recently, a special executive meeting in The Hague to discuss this. And the OPCW has been in contact through their Syrian ambassador in The Hague about what’s going on. The inspectors will no doubt go into Syria now. I would expect sometime in the next month, and hopefully sooner, to investigate these recent lapses, what the Director General Arias calls gaps and discrepancies in the declarations of Syria. And I think, if all goes well, Syria will be a full-fledged member of the CWC and regain its lost privileges. Three years ago, all its privileges in the CWC were taken away from it. It couldn’t vote, couldn’t join any committees, couldn’t obtain any positions in the OPCW at all.

So that’ll be a big step forward. And I also think it’s a big step for the Middle East in general. Once Syria is fully on board and there are no more chemical weapons and no more chemical offense program in Syria, I think it puts enormous pressure on Israel and Egypt to come on board and begin a process of full implementation in the Middle East of abolition of weapons of mass destruction.

Mark Leon Goldberg: That’s interesting. So, it could create some political momentum for the regional abolition and even put pressure on Egypt and Israel to join the OPCW, even though both countries have been extremely hesitant to do so.

Paul Walker: I think it’s, and I’ve said this to many Israeli colleagues, I think it’s much to their benefit to get themselves on board. I can’t imagine Israel using chemical weapons against anybody. I think they can’t either. And it would be important for the OPCW, for the treaty regime to get them on board. Whether the Egyptians would then follow, because the Egyptians, of course, also tie this to nuclear weapons, and Israel’s not a member of the Nonproliferation Treaty, so it might not bring Egypt on board. But I can’t imagine Egypt using chemical weapons either. So, it’s just as well to get on board. It’s an advantage to their foreign policy, it’s an advantage to their international relations, and I think would serve the whole world well.

Mark Leon Goldberg: So, one of the reasons, like the Syria use of chemical weapons was so shocking was just that the sheer number of people killed in that Ghouta attack, about 1300 people. But also, just the fact that there has been this, not just prohibition against using chemical weapons, but really a norm that’s been established and entrenched in international affairs for so long. And this was just such a shocking and outlier case. Another outlying case, and one that proponents of the treat, many state parties of the treaty as well have accused Russia of violating the treaty in poisoning the ex-spy Skripal and his daughter in an attack in England in 2018.

Can you just explain what we know about what happened in that attack and what the international response was in the context of invoking the Chemical Weapons Convention?

Paul Walker: Sure. I mean, the other country, which other than Syria has been shown to be using chemical weapons is Russia. That doesn’t mean they have large stockpiles. I’m convinced Russia doesn’t have any large stockpiles of chemical weapons. I was at every stockpile, and I can guarantee that every stockpile was fully destroyed. But they do have laboratory samples. That’s allowed under the treaty. And all you need is a laboratory sample for these individual assassination attempts that Russia is making. In 2018, two agents came to England and tried to kill Sergei Skripal. Skripal was a Russian agent years ago and had retired in England.

And I think Putin doesn’t seem to forget anything that goes against Russia. So, they had his name on some blacklist in the Kremlin. The agents came and smeared a nerve agent called Novichok, which is a novel nerve agent, very strong. Research on it started in the 1980s, but something that Russia had never declared. And they smeared it on the front door handle of Sergei Skripal.

And he and his daughter, Julia, were found on a park bench one afternoon frothing at the mouth. Luckily, emergency services got to them soon enough, and they both survived. But they declared that this was some sort of a nerve agent proliferated throughout the house. He must have put his hand on the door handle and then his hand touched everywhere in the house. Cleanup costs were over $50 million as I recall. It shows the challenges of dealing with the poisonous nature of these chemicals. The Novichok nerve agent was apparently in a perfume model and was subsequently thrown in a dustbin and picked up by a fellow who thought it was perfume and given as a present to his girlfriend, and she used it as perfume, and she subsequently got sick and died.

The perpetrators of it were pictured, pictures of them all over England in London and flying in and out and then went back to Russia, and were declared guilty of assassination attempt, but have not left Russia, to the best of my knowledge, and nothing was decided there. And subsequently, the Russians have tried to poison Navalny in 2020.

Mark Leon Goldberg: We have some breaking news now. Germany says it has unequivocal proof that Russian opposition leader, and Putin critic, Alexei Navalny, was poisoned using a nerve agent. Navalny is currently in an induced coma while being treated in Berlin. His wife and colleagues had alleged that he was poisoned while traveling from Moscow to Siberia last month.

Paul Walker: He survived as well. All of this has come up at the annual conference of the state’s parties at the OPCW and The Hague every year. The Russians still deny that they have done any of this at all. But I think it’s been proven that they’re actively using chemical weapons, not in mass attacks, but in discreet assassination attempts. It’s also been raised this December at the OPCW as a problem that Russia has now used riot control agents such as tear gas in the war in Ukraine. And that’s been pretty well proven, although there are more inspections going to take place under the inspector of the OPCW. So, you can see anywhere chemical weapons are alleged to be used, it’s important that the OPW inspect and prove that chemical weapons were used and actually who the perpetrator was.

It’s not an enforcement agency. There’s no enforcement under the OPCW. But I think Russia and Syria have to basically clean up their act and begin to abide by the treaty before anything more serious takes place.

Mark Leon Goldberg: And I think it’s probably safe to assume that Syria will likely, eagerly, abide by this treaty. The new de facto authorities there seem very eager to want to earn the good graces of the international community. And so, it would seem that having them invite and work cooperatively with the OPCW to destroy and identify any remaining stockpiles is a good way that they could demonstrate their seriousness of intent in running a different kind of regime in Syria. The Russia case is a little different, I think, now. For one, as you said, we’re not talking about stockpiles. These are just individual assassination attempts. And two, Putin is going to do what Putin wants to do, given like heightened geopolitical tensions.

So that the cases, at least to me, are very distinct. I wanted to ask you, what comes next for the Chemical Weapons Convention? You had this major milestone in which the last remaining stockpiles have been destroyed, seemingly inching us closer towards that top line goal of total abolition of chemical weapons. How can the convention continue to iterate as technologies develop as international relations unfolds in sometimes unpredictable ways?

Paul Walker: Yeah, that’s a good question, Mark. We just came from the annual meeting, the 29th conference of states parties in The Hague. And this was raised in our CWC Coalition, which is a global network, also just raised this in a couple of workshops, and we’re producing six papers on this in January. First of all, as we have discussed previously, you want to reach as fast as you can for universality, every country on board and every country abiding by the treaty, unlike Russia and Syria today. Secondly, you want to keep pushing the state’s parties for national implementation. And by that, I mean every state party is obliged to create a national authority, what’s called the NA. And this National Authority is particularly a committee under the Department of State or the Foreign Ministry can implement the treaty anyway it wants, or anything that happens in country is done by that national authority. And the countries also should legislate the treaty, whereby you can use it for prosecution purposes to prosecute individuals, non-state actors, if you will, terrorists.

Mark Leon Goldberg: Has that happened? Have there been examples of states invoking the Chemical Weapons Convention in domestic legal proceedings?

Paul Walker: They have in the United States. There are several cases where individuals tried to kill their partner or their wife or their husband using castor beans, and that’s gone into court, and they’ve been prosecuted. I don’t know if it’s happened too much abroad.

Mark Leon Goldberg: Well, that’s fascinating. I mean, you often think of these treaties as, particularly the Chemical Weapons Convention, as impacting state behavior in the context of them not using chemical weapons and destroying declared stockpiles to make the world a safer place. You don’t often think of states invoking the Chemical Weapons Convention in domestic violence cases.

Paul Walker: As a prosecutorial tool.

Mark Leon Goldberg: Yeah, but it’s there, apparently. I mean, that’s another long reach of this convention that I hadn’t really considered.

Paul Walker: No, it’s very important. And I think more and more as we see terrorists, like the Aum Shinrikyo in Japan in the 1990s.

Mark Leon Goldberg: Yeah, this was a subway attack in which they used sarin in the late 1990s, this kind of religious movement, and killed a bunch of people in a subway attack.

Paul Walker: And I think in Syria too, as you see ISIS or al-Qaeda trying to use chemical weapons. They’ve used chemical weapons at least, what? Three or four times, proven by the OPCW now in the civil war going on. You’d want to be able to prosecute them in Syria. That’s another issue. Well, I should say national implementation is about 50% of the state’s parties, which are not fully nationally implemented yet. So, there’s a lot of work to do there. Another issue and priority is the role of science and technology with the chemistry and chemicals. Chemistry is a very fast-evolving field of science. And there are about, I think, someone said 80,000 chemicals a year coming up, newly found. Artificial intelligence has something to do with that too. I think recent example was a fellow who, here in the United States, who asked his computer, his AI system to find toxic chemicals for him.

And by the next morning, just working overnight, his computer came up with 40,000 options. It doesn’t mean anyone’s going to produce those, but 40,000 formulas of chemicals. So, there’s always more toxicity in new chemicals coming along. And that’s got to be readily enforced. The OPCW has a scientific advisory board, which is quite good and helps, and they have a citizen’s advisory board on education and outreach, ABEO it’s called. And that’s also working quite well. I think public outreach, science and technology, public support, it’s only as good as the state’s parties are and they’re working on trying to get all state parties on board, even though 50% or more of the countries have never dealt with chemical weapons at all.

And they’ve got to beef up their inspectorate and beef up industrial inspections. They still have not inspected every necessary industry around the world, and they’re over 25 years old now. So, there’s a lot of work to be done, and I think keeping the inspectorate very much up to challenge inspections at any time, any place, anywhere, is probably also one of the key goals that set for itself today.

Mark Leon Goldberg: Paul, thank you so much for your time and, frankly, for your personal involvement in helping to rid the world of chemical weapons. Thank you.

Paul Walker: Happy to speak with you today, Mark.

Mark Leon Goldberg: Thanks for listening to Global Dispatches. The show is produced by me, Mark Leon Goldberg. It is edited and mixed by Levi Sharpe. If you are listening on Apple Podcasts, make sure to follow the show and enable automatic downloads to get new episodes as soon as they’re released. On Spotify, tap the bell icon to get a notification when we publish new episodes. And, of course, please visit globaldispatches.org to get on our free mailing list, get in touch with me, and access our full archive. Thank you!